The Revd James Sampson-Foster writes about being a reconciling presence in a divided world.

Before I came into ministry, I taught politics at a university.

In the study of politics, there are different models of party competition.

Within these models, there is the idea of there being a median voter. This is the idea that most people have shared ideas of what is most important in a society. There will be some who disagree, but they will be fringe voices.

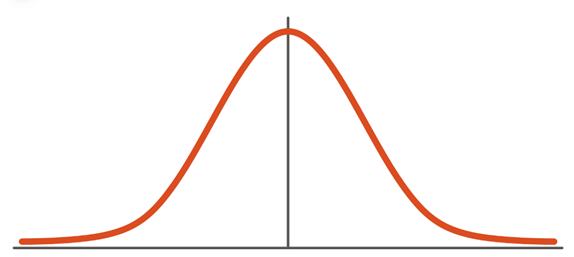

The idea of the median voter can be imagined as a bell-curve – like the one below - where the ideas and opinions of most people converge towards a kind of political consensus.

In this situation, dialogue is easy, because people share common values and speak a similar language. They may disagree, but they inhabit a shared world. Leaders and political parties trying to win elections move towards the centre of politics, competing to show people that they will be the best at doing the things that most people care about.

Certainly, for a time, the bell-curve gave a good illustration of the social reality of countries like the United Kingdom, but over the last decade, here and across the Atlantic, this has changed. Society has become more divided.

People now disagree profoundly on the values that are important in society. There are fewer shared ideas. People feel as though they inhabit different parallel worlds.

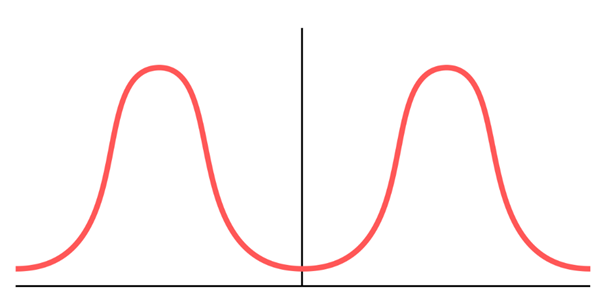

This new, troublesome, reality can be illustrated with a different graph like the one below.

In a society that looks like this, dialogue and compromise is very hard. Those seeking power and office, instead of appealing to a shared reality, appeal to extremes. Beliefs that may have previously been on the fringes become commonly heard.

Societies that look like this are changeable, dangerous and volatile.

What is the call of Christians within all of this?

Sometimes, Christians are called to be the fringe voices, off to the side of the bell-curve, challenging a consensus which needs to be upset. Faithful Christians have done this throughout all of history - the fact that priests are regularly arrested for climate activism shows that this tradition continues to be alive and well. Their work is an important reminder of the need to safeguard creation - the physical world we share together.

But sometimes, especially if society has become divided, there is another equally important call for Christians.

In a world such as this, it would be easy for Christians to simply offer another, holy, brand of division.

I do not think this is our call. Our call is to reconcile.

Our call is one of speaking a truth which is deeper than our divisions. Our call is to remind people of their shared values, their shared humanity, and the shared world they inhabit together. Our call is to put the common back into the common good.

But to be reconcilers in the world, we must also be a reconciling church.

Being a reconciling church is different from being a reconciled church. With its own history of division, the church knows little about being reconciled, but it knows a lot about the lived reality of reconciling.

It is in the lived reality of reconciling that the church participates in the movement and reality of the God who reconciles all things to himself.

In a divided world, it is precisely the reconciling church’s experience of love across its own divisions which enables the church to be a gift to others.

The body of Christ is wounded by our divisions, but by the wounds of Christ are we healed.

Through hard hours of dialogue and disagreement, we have learned reconciling habits of how to live fruitfully among difference.

We have learned to be curious – to listen to the stories of others and to see the world through their eyes.

We have learned to be present – to make ourselves available to others and making room for true and authentic encounters.

Most of all, we have learned how to reimagine - to look for hope and opportunity for positive change.

Our call is to be reconcilers – these habits are our gift to a divided world.

James is Assistant Curate at St Andrew’s Church, Rugby. Before ordination, James received a doctorate in Politics and International Studies and worked for the University of Warwick and Coventry City Council. James lives with his family in Rugby and his hobbies include miniature wargaming and playing the Hurdy Gurdy.